Home Built Cameras for a Conceptual Support

Home Built Cameras for a Conceptual Support

Unknown author. Kodak box camera, circa 1890

Unknown author. Kodak box camera, circa 1890

Having recently embarked into a deep metaphysical concept, one that is engaged in a personal and cathartic journey of self-discovery, I needed a camera system that would support such an endeavor. Following some experiments with a regular 35mm DSLR, as well as some exotic medium format digital systems, it quickly became apparent that a perfect camera system would not fulfill the ephemeral nature of the images desired to illustrate such a complex project.

The key components sought for these photographs involved a round image format, as a temporal disconnect akin to the first Kodak box camera of the late 1800’s, and the soft focus dreamlike quality of the pinhole mechanism.

Image # 2: Custom fabricated medium format digital camera

Image # 2: Custom fabricated medium format digital camera

With these precepts established, a custom built camera was undertaken, consisting of a flawed medium format digital array (Phase One P25 with dead pixels and a non functioning back display), a brass pinhole mounted on a 1960’s view camera shutter (that only opens and closes without the regular shutter speeds) affixed to the drilled protective plate supplied with the digital back. This system produces round images due to the close proximity of the wide-open shutter to the array, a soft rendition of the scene from the pinhole and even more interestingly some unpredictable aberrations due to the capture process that involves a dual firing of the shutter, the first to “wake up” the digital back that does not communicate with this mechanical only system, and in rapid succession a second capture for the actual image recording.

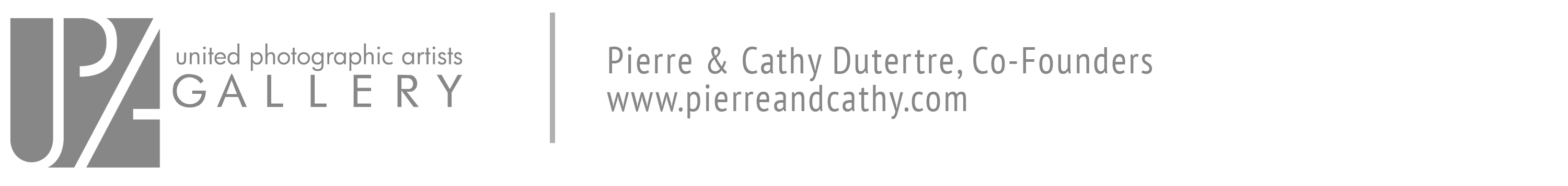

The following image clearly shows the results from the twin exposures, the unpredictable aberrations that add a chance element to the photographs, as a subtle reference to alternate planes of reality.

Cathy Dutertre. Disemboweled, “Quest” series, 2013

Cathy Dutertre. Disemboweled, “Quest” series, 2013

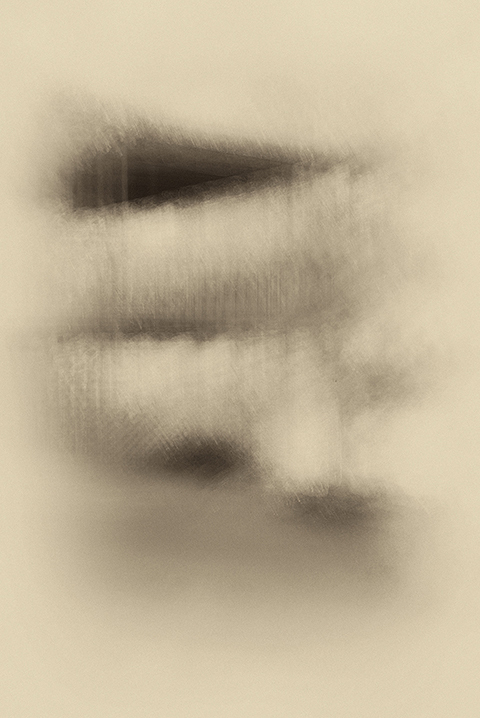

Another aspect of this custom camera resides in its propensity to suffer from extreme flare, a flaw that can then utilized for expressive purposes with the addition of artificial battery powered lighting on location (continuous or flash) projected directly into the pinhole opening.

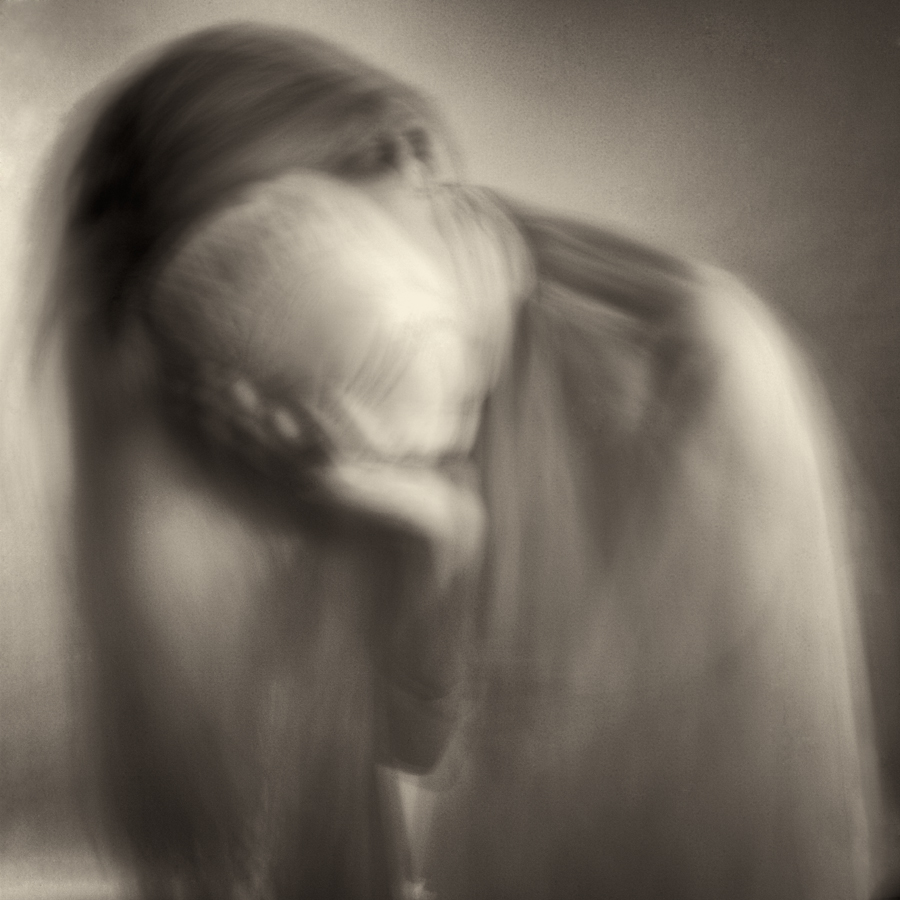

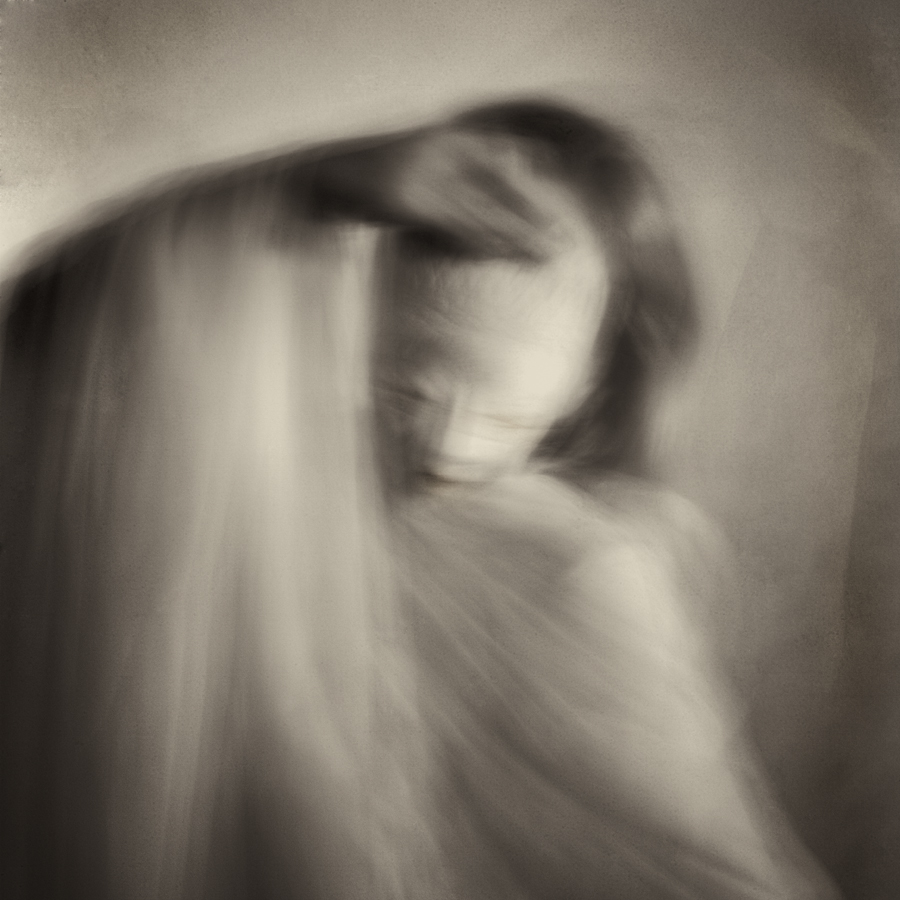

Cathy Dutertre, Deity, “Behind the Veil” series, 2014

Cathy Dutertre, Deity, “Behind the Veil” series, 2014

In addition, the absence of a viewfinder and the lack of a functioning back display means that the operator has no way of knowing if the subject, in this case myself as a self-portraiture approach, is actually in the frame and compositionally correct within the environment. This additional chance element allows for a slow and methodical process, one that required much experimentation in order to pre-visualize the camera’s field of view. Finally, the color palettes generated by the pinhole can be surprising depending on the quality and intensity of the light at the time of capture, resulting in images that either work well within the concept’s narrative or not at it is often the case.

Cathy Dutertre. Loss, “Quest” series, 2013

Cathy Dutertre. Loss, “Quest” series, 2013

As in all concepts, the tools utilized to generate images that support the project must be derived from the “What” and “Why” aspects, the intellectual approach needed to achieve a cohesive series of photographs that contain the visual elements supportive of the artist’s intent. In this case, this “round” pinhole camera has proven to be most effective with these communicative efforts, yet complex to operate, unpredictable for the most part, a magnet for dust that needs cleaning several times a day, but always wonderfully surprising, as photography should be, and was in the analog realm.

Photo Credit: Edgerton Harold

Photo Credit: Edgerton Harold Photo Credit: Richard Copeland Miller

Photo Credit: Richard Copeland Miller Photo Credit: Richard Copeland Miller

Photo Credit: Richard Copeland Miller

Photo by Cathy Dutertre, 2014

Photo by Cathy Dutertre, 2014  Photo by Cathy Dutertre, 2014

Photo by Cathy Dutertre, 2014 Photo by Cathy Dutertre, 2014

Photo by Cathy Dutertre, 2014

Recent Comments