Concept based photography versus randomness or the chance element, Part 2

In the first part we explored the foundational keywords associated with formulating a concept, The What and The Why.

In this section we will focus our attention on The How and The Who, namely how is the medium of photography specifically used to create images that support the overall concept, and finally who is the audience for your work and what type of presentation is needed to completely resolve your concept.

The HOW is a crucial process in the full realization of a concept, choosing the right tools and methodology in order to create photographs that are completely substantiated by a specific process. Rather than using whatever tool you have at hand, as a convenience approach, one must be able to decide what aspect and limitations of the medium are most appropriate to your conceptual involvement. In other words, perhaps a film based camera system may yield the results sought, over a perfect and sleek 35mm DSLR, or an alternative process such as Cyanotypes, Van Dyke Browns, platinum prints, the wet collodion process and so on could enhance the aesthetics and linguistic message embedded in your concept approach. A good example of such a radical approach can be seen in the wet collodion images of Sally Mann, with their eerie and mournful exploration of the past culture of the Deep South. The optical and physical flaws of the process are embraced by Mann to imbue a sense of time deconstruction and nostalgia.

Sally Mann, In The Deep South, 1996, wet collodion process

Sally Mann, In The Deep South, 1996, wet collodion process

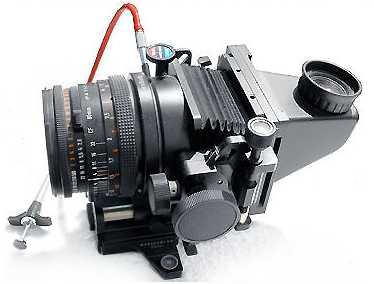

Keith Carter is another established artist who uses a rare system made for architectural photographers years ago by Hasselblad with the ability to swing, shift and tilt the front lens in order to correct extreme perspectives. However, Carter uses this camera to precisely create narrow fields of focus in the scene for expressive and creative purposes.

Keith Carter, young stallion, 1998

Keith Carter, young stallion, 1998  Hasselblad Flexbody system{C}

Hasselblad Flexbody system{C}

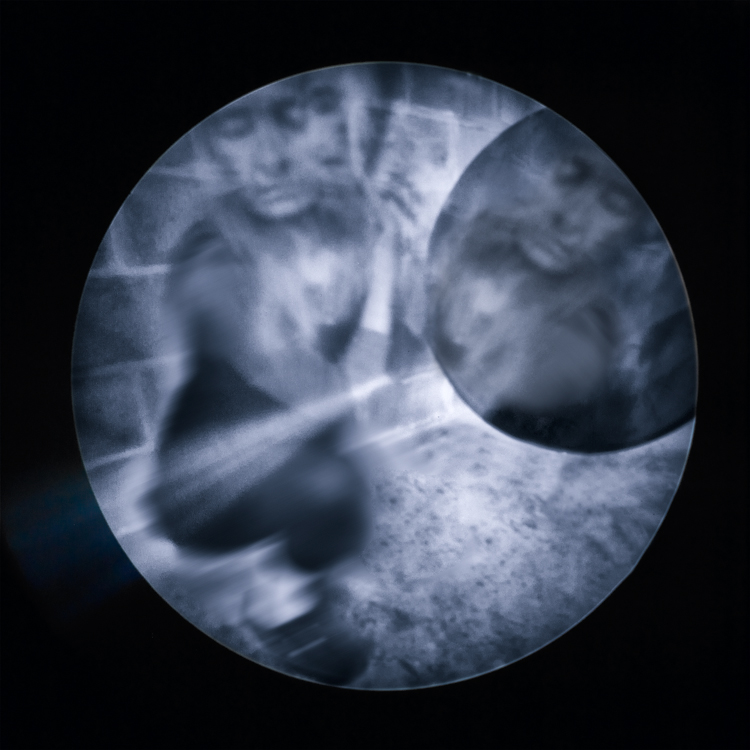

The expressive and moody nature of Carter’s images was reinvented for my Deep Forest project by creating a medium format digital camera that replicates the Hasselblad system, using several flawed components, an older digital back with the whole system not designed for in the field use. Yet, the aesthetics created by this home-assembled camera were the exact results needed to support the narrative and medium-based conceptual intents, not an easy task but one needed to effectively articulate my concept visually.

Pierre Dutertre, Fright, 2012{C}

Pierre Dutertre, Fright, 2012{C}  X2Pro with flawed Phase One P25 back, broken Mamiya RZ lens

X2Pro with flawed Phase One P25 back, broken Mamiya RZ lens  Cathy Dutertre, Foresight, 2013

Cathy Dutertre, Foresight, 2013  Homemade pinhole medium format digital camera

Homemade pinhole medium format digital camera

There are an almost infinite amount of decisions to be made when resolving the HOW:

What kind of focus will you be using? Sharp, soft, out of focus, partial planes of focus?

What kind of time? Frozen or slow shutter speeds, long exposures?

What kind of camera? Analog or digital, 35mm or larger formats, toy cameras, home made cameras? Flawed systems? Pinhole?

Black and White photographs? Color? Manipulated colors? Polaroid?

What vantage points?

What kind of light? Hard, bright or subdued? Night photography? Inclement weather?

What kind of compositions? Busy or quiet? Frenetic or silent?

What kind of framing? Active or passive?

As with other decisions made during the concept planning stages, the HOW is often a complex approach requiring research, innovation and some budget. Most likely you will need to experiment with the aesthetics of the images until you arrive at the perfect solution to resolve your visual intentions. In my case, it took almost a full year before I was able to build a system that allowed the desired aesthetics to support my narrative, after experimenting with view cameras, perspective correction lenses and a lens baby that was simply too imprecise.

Last, We also need to resolve the WHO, namely your audience and presentation. Knowing your audience before you begin a project can be a difficult task if the concept is medium based, such as abstractions or classical landscapes, thereby of appeal to the masses, as opposed to social documentaries, environmental issues or a feminist / gender bias, in which case your audience may be more refined. Ultimately, one needs to discern if your audience is clearly refined and in which geographical areas, where are they likely to view your work and who is potentially a buyer or collector of your work.

The location for the presentation of your images will impact your display decisions: Are you seeking a large gallery space? A museum? An intimate location? Are you printing your images very large for a visual impact? Or very small for an intimate connection with your audience? Are you going with a classic framed presentation or an installation? What kind of lighting are you faced with in the exhibit space?

These decisions are also likely to affect your choices of equipment, insofar as printing an image at 6’ by 10’ will likely require a high end medium format camera for the original capture whereas a 10” by 10” print from a cell phone could work equally as well. This leads us to consider the all important budget question. The greatest portion of your financial decisions when developing a concept resides in the final presentation method. An average size 20” by 20” print, matted and classically framed to 30” by 30” can cost around $300 plus, much more if you use the exotic but amazing Optium optically clear acrylic glass at around $600 per frame. If you have a solo show at a gallery with say 30 pieces, your initial investment is around 18K plus shipping, insurance and packaging. Again, this kind of research is important to refine during the concept development, but not as a roadblock necessarily. Cheaper presentation solutions are available and digital only showings are perhaps appropriate, although I am a firm believer that photography is never quite finished until it is printed as a firm and permanent surface for viewing. I would also say that presentation is a key link on how a concept is viewed and received by your audience, yet that step is often ignored altogether by emerging photographers who scramble at the last minute after their work is accepted into a show (crowd funding is slow and unpredictable for such a posit).

Cathy Dutertre. Installation using large images printed on semi transparent fabric, suspended by steel cables in a 3-dimensional space, back and front lighting, multiple heights and free standing. The passage of the viewer between the images will create a gentle wind motion and a soft sway of the prints.

Cathy Dutertre. Installation using large images printed on semi transparent fabric, suspended by steel cables in a 3-dimensional space, back and front lighting, multiple heights and free standing. The passage of the viewer between the images will create a gentle wind motion and a soft sway of the prints.  Pierre Dutertre, classic framed presentation, captured in the environment.

Pierre Dutertre, classic framed presentation, captured in the environment.

In conclusion, what separates a confused photographer from an emerging artist resides firmly in the application of a concept onto the work produced. From random images (nothing wrong with great single images, as they may well lead to a subsequent concept) to a body of unified and intellectually resolved images, lies the process of establishing a concept for your work, a direction or operations manual. It does not need to be a roadblock, or an impossible pre-visualization, an unwanted school essay or a tedious task. It however needs to be established BEFORE you begin creating images, as the only path to creating bodies of work that will surely help you grow artistically and intellectually within the medium. Your intellectual and research investments in creating a solid concept(s) will always result in growth and surprising outcomes on many occasions.

Now, let’s see you become image-makers, rather than image takers.

Pierre Dutertre conducts extensive workshops, entitled Journey Through Personal Creativity, on the topic and application of a concept based approach at the Florida Museum of Photographic Arts.

Posted by Pierre Dutertre in concept-based photography

Pierre Dutertre, Weeping, Deep Forest concept, 2012

Pierre Dutertre, Weeping, Deep Forest concept, 2012 Pierre Dutertre, Barren, Deep Forest concept, 2012

Pierre Dutertre, Barren, Deep Forest concept, 2012

Recent Comments